Route 91 Harvest Festival

Every fall since 2014, the Route 91 Harvest Festival has transformed a 15-acre concrete plot on Las Vegas Boulevard into a lively, three-day country music party. The open air music festival has always seemed both at peace and at odds with its surroundings. Las Vegas, known as the entertainment capital of the world, is a desert outpost for the everyman and everywoman—a place people of all ages and backgrounds flock to eat, drink and play. In this sense, Route 91 and its concertgoers fit right in. And yet, at the same time, they don’t. Tucked into the shadow of the Mandalay Bay Resort, a 43-story shimmering gold monolith, Route 91 is more like a backyard house party for the cowboy hat-wearing set than a reflection of the opulence and overindulgence surrounding it.

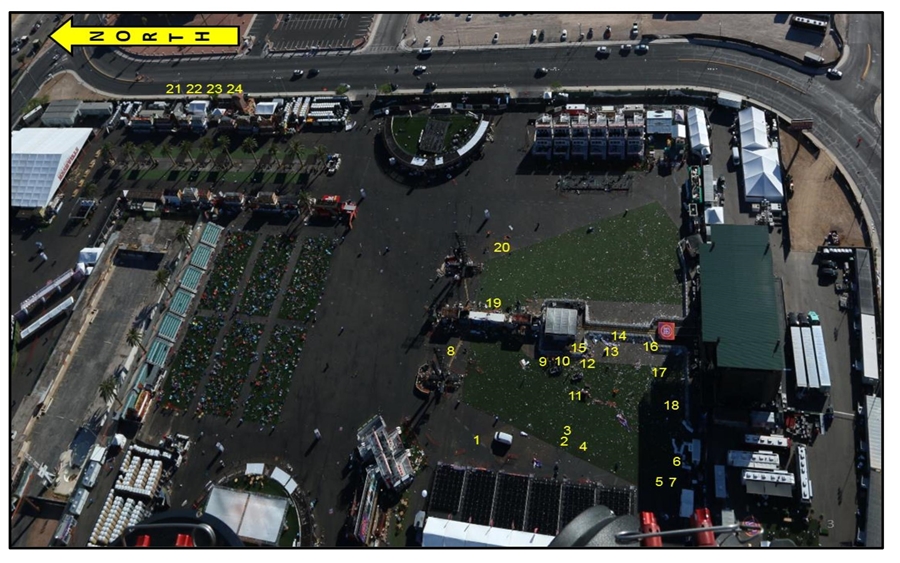

The Site, from the LVMPD Report

A tall chain link fence with dark netting surrounded the venue last fall, and there were two entrances and two exits, according to people who were there. A three-day general admission pass cost $210, and VIP packages ranged from $375 to $750. Children under six got in for free. It’s important to remember what the event was all about before a man opened fire on the crowd: people coming together to enjoy the best of country music. Videos and photos posted from the weekend show friends smiling for selfies, loved ones holding hands, people drinking, partying and singing together.

Sunday, October 1, 10:08 p.m.

Chris Babij, his wife, Jenny Mark-Babij, and a friend wandered towards the main stage to watch Aldean’s finale, leaving the rest of their group at the chair corral in the back of the venue. Babij, a call center manager for CIT Bank, and Mark-Babij, a costume stylist, met online in 1999, married three years later, and settled in Southern California. They’d never been to the Route 91 Festival before, but Babij had recently discovered country music, so they decided to kick off their annual fall vacation with a long weekend in Las Vegas. Next stop: Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.

When Babij heard those loud pops, he remembers turning to his wife, saying, “Who’s lighting off fireworks?” The truth, they quickly realized, was far more terrifying. Those sharp cracks were gunshots, and a few seconds after squatting on the ground, one of them hit Babij’s shoulder. “I was ducking down for cover thinking I was doing the right thing and I still wound up getting hit,” he said. “It felt like someone came up behind me and punched me in the kidneys.”

“Chris said to me, ‘I think I’ve been hit!’” Mark-Babij recalled.

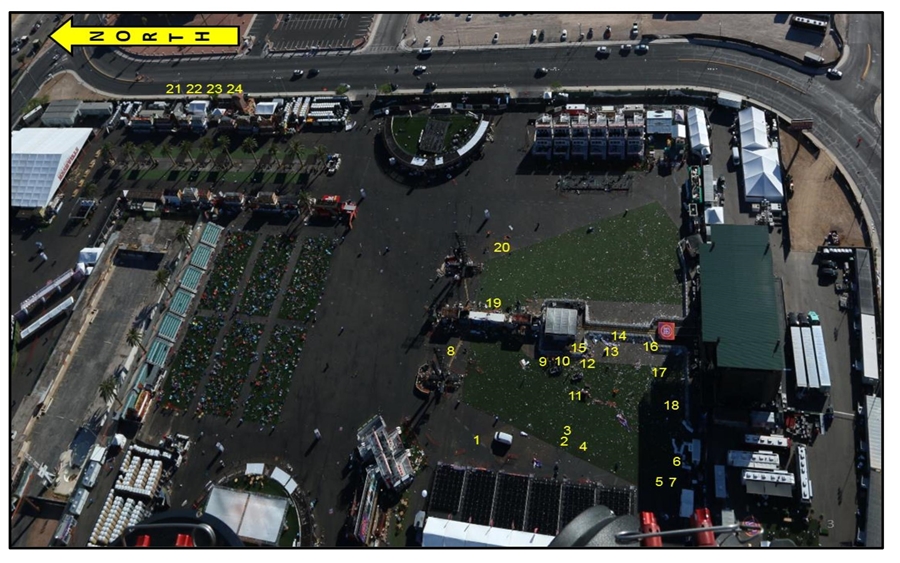

Locations Of Deceased Persons, from the LVMPD Report

They scrambled under the soundstage and hid for at least five minutes, listening to bullets smack into bodies and equipment all around them. “I tried to stay calm and pray and comfort myself and figure out our next move,” said Babij. It wasn’t until months later, when the official police report came out, that they realized they’d been standing in the middle of one of the deadliest areas during the shooting.

Suddenly, they heard a break in the gunfire. Time to move, they thought. Mark-Babij crawled out from under the soundstage, grabbed her friend’s hand and ran. She thought Babij was behind her but—

“It was almost a scene out of the movie,” he said. “My left leg got caught in a wire, so there was a delay. That’s how we got separated. Jenny ran with our friend. I said, ‘Just go! Just go!’ I knew they had to get out of there. It’s like the horror movie where you’re trying to fumble to get the keys to your car. My leg was stuck in a wire! My arm was like a noodle! Finally, I got free and just ran.”

Locations of Deceased Persons, from the LVMPD Report

Despite more than 50 Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (LVMPD) personnel working the festival, the scene has been described as total chaos. Police initially believed the shooter was in the crowd. “It wasn’t until two officers were shot at the Mandalay Bay in the crosswalk, with wounds that come down their body, that police realize he’s above them shooting out the window,” said Julia Pierson, former director of the U.S. Secret Service. “He has muzzle deflectors on the rifles. He’s back in the room and police on the ground just couldn’t see him from their position.”

There were no formal announcements as to what people should do, so concertgoers ducked, ran, screamed, hid and tended to the wounded. “You were a rat in a maze,” Babij said. “To prevent fraud and make sure people paid for their tickets, there were only two entrances, VIP and general admission. Fences were toppled over and people made their own exits. That was one of the bad things, the design.”

After hiding behind trucks and cars, Mark-Babij and her friend fled to the Hooters casino, about three-quarters of a mile from the festival. Babij wound up at the MGM Grand, a few blocks farther. “To me, Hooters was too close,” he said. “I wanted to be as far away as possible.” In the lobby, he slumped into a chair and told a paramedic he’d been shot. “She’s looking at my body, because I didn’t have an exit wound or blood. I went like this,” he said, pulling his shirt over his back. “She’s looking around and she goes, ‘Shoulder!’ And that’s where I saw the hole in my shoulder.”

He watched the paramedic scribble “GSLS” (“gunshot left shoulder”) on a piece of paper and place it on his lap, along with his license and phone. Moments later, someone ran into the lobby shouting, “The shooter is coming this way!” Misinformation and rumors spread quickly in the chaos, and while Babij had no idea if a gunman really was nearby, he didn’t care; he bolted out the back of the hotel, his left arm flopping against his body, and kept running until a couple in a white SUV pulled over and offered to drive him to the nearest hospital.

The rest of the night unfolded in hazy flashes.

Babij remembers sitting in a large room with other gunshot victims at Desert Springs Hospital, repeating his name to over a dozen doctors and nurses. Staffers walked around putting tags on patients—red for critical, yellow for urgent, green for not urgent. His tag was yellow. Periodically, someone mopped blood off the floor.

Meanwhile, Mark-Babij was hunkered down at Hooters, waiting to hear from Babij, wondering where her husband was and whether he’d really been shot. She didn’t sleep that night.

Monday, October 2, 1:00 p.m.

After receiving a text from the couple that drove Babij to the hospital, Mark-Babij spent hours trying to call him. But every time someone picked up at the hospital, she was told to try again in three hours. “Those hours felt like days, even weeks,” she said. “Eventually I learn he’s been put in a room. My call gets transferred up to that floor, but they said, ‘We don’t have anybody by that name,’ and they sent me back to emergency.”

That back-and-forth continued until, finally, she got through to Babij. “I said, ‘Are you okay?!’ and he said, ‘Jenny, I was shot!’ It wasn’t until that moment that I really knew,” Mark-Babij said.

Monday afternoon, 15 hours after the shooting, they were finally reunited. When Mark-Babij reached her husband’s hospital room, he was in excruciating pain. A bullet had fractured his humerus bone, she learned, scattering bullet and bone fragments in his rib cage. There was no exit wound. The doctors said they’d have to wait until the swelling decreased to consider surgery, and that could take a week.

Babij and Mark-Babij were exhausted, scared and overwhelmed. Now they were facing another week at what they called “ground zero,” far away from their doctors and friends. They didn’t know how they’d be able to go on.

Monday Evening

After visiting Babij at the hospital, Mark-Babij headed back to their hotel room—on the 26th floor of Mandalay Bay, six floors below the shooter. She’d been awake for a day and a half straight. “My Uber dropped me off by the Delano Hotel, because my hotel had been taped off as a crime scene,” she said, her voice shaking. “I was forced to walk through the casino to get back to the room. It was empty, and very eerie. I felt very scared. That was a very traumatic moment for me.”

Mark-Babij instinctively knew she’d endured her own trauma at the festival, just like tens of thousands of other concert goers who’d survived the attack physically unharmed. But for the moment, she didn’t have time to focus on herself. She closed the blinds, blocking out the nightmarish scene below, ordered dinner, and started plotting how to transport her husband back to California for treatment.

Tuesday and Wednesday, October 3-4

For two days, Mark-Babij says she battled their health insurance provider to cover the trip home. “Because Chris’s situation was not life threatening they would not approve air transport or ambulance transport,” she says. “So after I found that out on Day 3, I asked the case worker, ‘what will it cost to hire an ambulance?’ She said $7,000. I said, ‘Make it happen.’”

But no ambulances were available for another 24 hours. She broke down sobbing. So did Babij. They couldn’t imagine spending another hour, much less another day or more, trapped in the city that had ripped their lives apart.

At that exact moment, two doctors walked into the room and asked what was wrong. When they explained, one of the physicians said, “If I were you, I would have been home 12 hours ago.” The other called in a prescription for morphine, and by 5:00 PM, Babij and Mark-Babij had piled into their car and set off on the four-hour drive across the Mojave Desert, towards home.

“I was completely shocked and traumatized,” Mark-Babij said. “I kept thinking, ‘How am I gonna make this drive? What if something happens to him?’ It’s pitch black in that desert! There were so many things running through my mind, but we made it.”

Around 9:00 PM, she pulled up to Arcadia and Methodist Hospital in Arcadia, California, and checked in her husband. Friends were already there waiting. After surviving the deadliest mass shooting in modern America, enduring three frantic days in the hospital, and driving four hours across the desert at night, she finally felt safe.

By Abigail Jones

© 2018